The Chicago Riots of 1919

Dan Bryan, May 20 2012

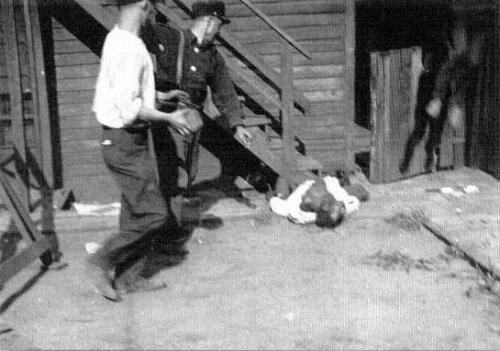

Two white men assault and kill a black man in the 1919 Chicago Riots

Two white men assault and kill a black man in the 1919 Chicago RiotsThe blacks swam on 25th street, the whites on 29th. Everything began from the inadvertent violation of that unspoken agreement.

The violence in Chicago began on July 27th and lasted for a week. Thirty-eight people were killed -- twenty three black and fifteen white. Only an infusion of state militia was able to quell the violence and restore order.

The 29th Street Beach

For those who lived on the south side, the beaches were divided between 25th and 29th street. Blacks used the 25th Street Beach, and whites used 29th Street. It was a typically hot summer in Chicago, and on Sunday, July 27th both beaches were packed. Feelings were inflamed that afternoon when a group of blacks tried to make use of the 29th Street Beach, and there was a big scuffle with several assaults and general anger on both sides, before the group of blacks was driven away. It wasn't a particularly noteworthy event, but it did heighten the atmosphere and put the racial problems at the front of people's minds.

Unfortunately, a group of black teenagers in a raft drifted over to 29th street later that afternoon, far out in the water. They did not know what had transpired earlier. Rocks and bricks flew at them and eventually one of the boys, Eugene Williams, was hit squarely in the forehead. He dropped from the raft into fifteen feet of water and drowned.

Again a crowd of blacks formed on the 29th Street Beach. A policeman refused to arrest the perpetrators, but did arrest another black man involved in the scuffling of that day. When a police wagon arrived to take the arrested black man into custody, a general fight broke out, with both sides hurling bricks at each other. Then a black man fired at the police with a revolver, and was shot to death.

Hundreds of people leave the 29th Street Beach on July 27th. Rumors quickly spread through the South Side.

Hundreds of people leave the 29th Street Beach on July 27th. Rumors quickly spread through the South Side.The Riots

It did not take long for the athletic clubs to hear about the 29th Street incident -- in versions that were twisted around to the rhetoric of a black invasion. It was known that blacks were gathering in anger in the Black Belt, and the athletic clubs went on a preemptive offensive that Sunday night.

John Mills had boarded an eastbound streetcar on 47th street. After traveling a few blocks, the car was disengaged from its line by a band of hoodlums. Mills and five other black men jumped from the car and ran as fast they could, but Mills was caught after four blocks and beaten to death on the streets. Several hundred whites stood on the sidewalk and cheered the proceedings, including some women and children.

Whites who ventured into the Black Belt were equally at risk. A peddler named Casmero Lazeroni steered his goods onto 36th and State. Obviously he underestimated the severity of the situation, for he was isolated and in great peril. Blacks threw stones and bricks at him until his wagon stopped, and then dragged him into the street and stabbed him to death.

The pattern for the next few days was that of the black community bunkered in their own neighborhood, defending it mercilessly against outsiders. Some who went to work on Monday were pulled off of trolley cars and beaten or stabbed to death. On Tuesday and through the rest of the week, they almost unanimously stayed away from their jobs -- since the commute required them to ride directly through the Irish neighborhoods. Few of them even ventured outside, given the circumstances.

Groups of Irish gangsters drove through the Black Belt in cars and fired at or assaulted any blacks who they saw, in one of history's first examples of the "drive-by shooting". Black men hunkered behind windows and sniped at these cars with revolvers and rifles.

A group of Irish men patrol their neighborhood with bricks in hand

A group of Irish men patrol their neighborhood with bricks in handThe police were singularly unable to maintain order. Those arrests that were made were overwhelmingly of the blacks -- very few of the Irish hoodlums were stopped. For two days, the mayor and the governor sparred with each other on the necessity of mobilizing the state militia. Nobody wanted to be seen as the first to order troops in against the Irish. So while the rioting flared on, Governor Lowden told the papers that he was ready to send in troops as soon as Mayor Thompson approved it, while Thompson reiterated that the responsibility rested with Lowden.

Finally there was no choice. Thousands of state militia were posted on the "color line" in the south side, ordered to restrict access to the area, and given very strong instructions to take the Irish gangs seriously. They coordinated food deliveries, helped transport trapped families to safer areas, and they cracked down on the athletic clubs. Since they were relative outsiders, they could see more clearly who the primary instigators of the problems were. In general, they comported themselves well given the trying circumstances, and were much more even-handed than the police.

Troops from the Illinois Militia guard a street after several days of rioting.

Troops from the Illinois Militia guard a street after several days of rioting.By Friday, August 1, things seemed to be in a much higher state of order. Then on Saturday morning a massive fire broke out by the stockyards, in the Polish and Lithuanian neighborhoods. Almost a thousand people were left homeless. The Irish immediately blamed the blacks, but the story that came to be accepted was that a group within the athletic clubs had painted themselves in darkface and lit the fires, in the hope of drawing in allies and expanding the rioting. Fortunately, the other immigrants were not drawn into the fray.

By the end of the weekend, open violence was at a minimum. The remaining issue was ensuring the safe transport of workers to their jobs at the stockyards.

The coverage and the aftermath

The Chicago press took the side of the Irish with vigor in the days after the riot -- even as newspapers in other cities made it clear that what had happened was mostly a white pogrom (no small concession to make in 1919).

There was tension at the stockyards had not been close to resolved by the rioting, but rather was inflamed further. For several days, thousands of troops escorted the trolley lines and remained posted on site, to defuse any violence between the two groups. There were assaults, to be sure, but a general battle did not break out again.

While one could obviously view this episode through the lens of racism, that would only tell part of the story. There were many groups arrayed in mutual antagonism, but only the Irish struck so violently. They rioted not as frenzied individuals, but together in their "athletic clubs", which operated with the tacit approval of political and community leaders. When they grew up, members of these clubs formed the core of the Irish political machine.

It is no coincidence that the Irish were so successful at preserving their neighborhoods and at winning elected office. Few groups mixed the legal and the extralegal so seamlessly in their quest for political power.

*See also: Prelude to a Riot -- Irish Athletic Clubs and the Black Belt in 1919*

Recommendations/Sources

- William M. Tuttle, Jr. - Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919

- The 1922 Report by the Chicago Commission on Race Relations