The Travails of Paul Robeson

Dan Bryan, September 11 2012

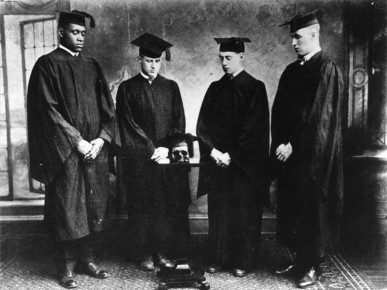

Paul Robeson was one of four students from Rutgers' Class of 1919 to be awarded Cap and Skull.

Paul Robeson was one of four students from Rutgers' Class of 1919 to be awarded Cap and Skull.In the annals of trail blazing personages must certainly be included Paul Robeson. In his early life he won selection to Cap and Skull and was the valedictorian at Rutgers. He obtained a law degree and played two seasons in the fledgling NFL -- simultaneously. As an actor he was the first African-American to ever star in a non-silent film.

This same man concluded life as a blacklisted Marxist, largely ostracized from even the ascendant Civil Rights movement. His first step toward this complicated legacy came in the midst of the Great Depression, when he accepted an invitation to visit the Soviet Union.

The early life of Paul Robeson

Let us look at the life of Paul Robeson in 1934. This man has excelled at academics from a young age, has graduated from Rutgers with high academic honors, has obtained a law degree from Columbia University, played two years in the NFL (before that league was segregated).

Faced with an overwhelming degree of racism in his practice of the law (this in the 1920s), Robeson has left that profession to become a musician and an actor. He possesses good looks and ample talent in both of these fields. He uses these to gain steady work and good contracts as the 20s give way to the 30s.

Paul Robeson as a star football player and later as an actor.

Paul Robeson as a star football player and later as an actor.By 1934 he has starred in a wildly successful run of Othello and in a controversial film called The Emperor Jones. The latter effort makes him the first black man to star in a non-silent feature film. He remains relatively non-political, arguing that his success alone stands as an indictment of white supremacy.

First travels to the Soviet Union

It was in this stage of his life that an official invitation was extended for Robeson to visit the Soviet Union. Part of the political strategy of the Soviet Union at that time was to highlight the repression that women and minorities suffered in capitalist countries. Sympathetic to far left politics, Robeson accepted.

On the way to Moscow, Robeson and his wife had a layover in Berlin. Here they were insulted and threatened by Nazi S.A. troopers in a way that left a deep impression on Robeson. In contrast, he was treated like an honored dignitary once he arrived in Russia. The difference in reception left him with little doubt as to where his sympathies extended.

"Here I am not a Negro but a human being for the first time my life... I walk in full human dignity."

Of course, the adulation that Robeson received in the Soviet Union was hardly spontaneous. Every friendly word on the street was a calculated gesture to win his esteem and approval. Every cheer he received at a public performance was choreographed. To the extent that these tactics worked they reflected poorly on the United States. For without the intransigent white supremacy of that country such gestures would have served no purpose.

After this trip Robeson proclaimed his fondness for the Soviet Union and for Joseph Stalin. Even much later in life, when all evidence should have indicated otherwise, Robeson held to these statements and continued to visit Russia. He faced the isolation and career-ending consequences of these views in the late 1940s, and lived for the rest of his years in straightened circumstances.

How much of a Communist was Paul Robeson? He was intentionally vague on this point. In 1956 he told the House Un-American Activities Committee, "Whether I am or am not a Communist is irrelevant. The question is whether American citizens, regardless of their political beliefs or sympathies, may enjoy their constitutional rights."

Racist alienation and political radicalism

Robeson was hardly the only black (or white) intellectual of the early 1900s to express sympathy for Marxism. Most famously, of course, there was W.E.B. DuBois and Langston Hughes. Hughes had actually traveled to the Soviet Union in 1932 to advise on the production of a film about racial and labor conflicts in Birmingham, Alabama (this film, which would have been a fascinating take on events, was unfortunately not completed).

White supremacists latched onto this sympathy for Marxism to discredit these thinkers. They hoped to use such attacks to sabotage the call for civil rights. Indeed, the stigma of radical leftism attached itself freely to many more black leaders over the coming years of struggle.

It is important to remember three things before deriding the embrace of Marxism among early black leaders such as DuBois and Robeson. First is that the theory had not yet been disproven in any way except the abstract. We know about the purges and famines of the 1930s. We know the ultimate wages of Communism as it was implemented in the Soviet Union. Did Robeson know of these things in 1934? Is it reasonable to infuse his thoughts with a degree of foresight which would have been required to ascertain those ultimate ends? Many things are only obvious after the fact.

Secondly, as individuals like Robeson took an interest in African issues, they saw nothing but a continent that had been colonized in checkerboard fashion by the powers of Europe. Did this not make a farce of the liberal, democratic, open economic ideal? Was it not a bit racist of some to look askance at a prominent performer who suddenly began speaking out on colonial issues? Has anti-colonialism not been at least somewhat vindicated by events since 1934?

Finally, the society of the American South at that time had hardly evolved from the seigniorial mode of living. Numerous facts have been repeated ad nauseum about Jim Crow but perhaps a small indignity tells the story better than a restatement of larger crimes. Established traffic law stated that whites held right-of-way over blacks automatically, in all situations where two paths might cross on the road or elsewhere. Life was rife with such symbolic, submissive gestures.

In a world where a man's law degree from Columbia University was rendered irrelevant by social convention -- how could that man not become "radicalized"?

Persistence of Robeson in old age

In spite of long list of American heresies, Robeson was eventually given a chance to join the mainstream of the Civil Rights movement -- a chance that was extended to him on the condition that he renounce Communism. He refused. From the early 1960s until his death he spent most of his time in retirement, living in Philadelphia.

Robeson's drift to the political fringe leaves many questions. Would most people in his situation have done the same, when confronted with the prejudice he faced? Should a performer's political views be considered relevant to their artistic legacy? For many years Robeson received almost no mention in stage and cinema histories, even though his run in Othello still stands as the longest of any Shakespeare play on Broadway.

Over time, as is wont to happen, these political apostasies have been downplayed while his considerable talents have been given emphasis. Even as he died, in 1976, newspapers gave him a more reconciliatory portrayal. Eventually his better movies were shown again on television, and in modern times his image has been largely rehabilitated. In a way, it seems all too easy to make amends on such a thing after everyone involved is gone. Is this "rehabilitation" (to borrow a Communist phrase) the full extent to which Robeson's story is relevant in modern times? Is it easier to apologize for (or glorify) the past than to acknowledge present failings?

Recommendations/Sources

- The Emperor Jones (full-length viewing)

- New Jersey Sports Heroes - Paul Robeson

- Blacks in the Soviet Union

- The Many Faces of Paul Robeson

- Forgotten Classics of Yesteryear - The Emperor Jones

- The Espresso Stalinist - "'I Am at Home': Paul Robeson at Reception in Soviet Union

- Paul Robeson - Here I Stand