Two and a Half October Surprises -- The Last Days of the 1968 Election

Dan Bryan, November 3 2012

It is hard to find an election that had a more volatile final week than that of 1968. A peace deal announcement and its subsequent sabotage, possibly by Richard Nixon himself, whipsawed the poll results in the final week of an election that was decided by less than one percent of the vote.

Yet curiously, these events are almost an afterthought in most retellings of events in 1968.

Hubert Humphrey's October comeback

Hubert Humphrey was supposed to have no chance in 1968. His own hotel room had been suffused with tear gas as he prepared his nomination speech. Seen as a stooge of LBJ in many quarters, Humphrey had left the Democratic convention trailing by almost twenty points in the polls ("As late as September 20 the polls showed Nixon with 43 percent of the vote, Humphrey with 28, and the Wallace-Curtis Le May ticket with 21"). Riots, assaults, and police brutality in the streets had made their indelible impression in the eyes of the world. Ironically in an election that also featured Richard Nixon and George Wallace, it was Humphrey who received the greatest amount of hate from the radical peace movements of America.

On the other flank of the Democratic Party, union members were deserting Humphrey in droves for the insurgent, segregationist candidacy of George Wallace. The consensus opinion was that Humphrey would barnstorm the country for a few weeks and give a heartfelt speech on election night, after being thoroughly demolished by Richard Nixon.

As October progressed though, Humphrey astoundingly pulled back into the race. There were three main causes to his comeback. Most importantly he began to sketch a position on Vietnam that was independent from that of Lyndon Johnson, including a notable speech in Salt Lake City in which he called for a bombing halt of North Vietnam. The speech almost immediately put the hecklers to rest and inspired genuine hope for Humphrey's candidacy among the dovish wing of the Democrats.

Union support rebounded thanks to a furious campaign by the AFL-CIO, which cut deeply into the share being polled by George Wallace. It is estimated that the AFL-CIO registered 4.6 million voters and distributed 115 million pamphlets to the American public, including 20 million specifically addressing the perils of Wallace's candidacy. Using modern computer and phone-banking technology to target voters, the AFL-CIO likely did more for Humphrey's ground game than Humphrey himself. In states across the Midwest and Northeast the labor unions single-handedly muscled Humphrey back into contention.

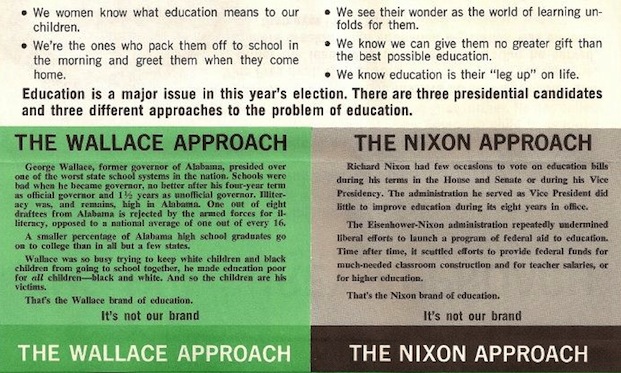

A union-produced piece of campaign literature, attacking Wallace and Nixon on the issue of public education.

A union-produced piece of campaign literature, attacking Wallace and Nixon on the issue of public education.Lastly, Richard Nixon refused to debate Humphrey. The rationale was to avoid a repeat of the 1960 fiasco against JFK, since Nixon had little confidence in his debating abilities. It was hoped that his large lead would render the issue irrelevant, but as Humphrey surged in the polls his attacks on Nixon began to catch on. Moderate voters began to take negatively to Nixon's avoidance of a debate against Humphrey, and this also contributed to the erosion of his support.

Gallup polls began to show that Humphrey was essentially tied with Nixon in the national polls. Commentators began to speculate that they were witnessing the most remarkable comeback in the history of American presidential elections. Such notions touched off frenzied excitement or utter despair, depending on one's leanings.

Johnson's game-changing press conference

Then with less than a week remaining before the voting, it suddenly appeared that things were clinched in favor of the Democrats. On Thursday October 31st, 5 days before the election, President Johnson gave a press conference announcing a breakthrough in the Paris Peace talks. Faced with the prospect of peace in Vietnam, voters responded with a renewed push to Humphrey. Nixon's advisers later asserted that had the election been held on that Friday or Saturday, Humphrey would have easily won. Such was the degree of the catastrophe facing their campaign.

Having worked for years to shed the reputation as a "loser", it now seemed to Nixon like he was about to squander one of the largest leads in the annals of campaigning. Had this scenario materialized, Nixon might be remembered today as a tragically star-crossed politician. It would have been his third major defeat in eight years.

However, the announcement of potential peace was not the last of the twists to occur in the 1968 election. The apparent turn in Humphrey's favor was soon followed by an equally sharp regression.

The foreign intrigues and sabotage of Anna Chennault

The savior of the Nixon campaign was Anna Chennault. A native of China and a high-level Republican operative, Chennault inserted herself into the proceedings by using her contacts with the government of South Vietnam. Assurances were given that a better deal would be forthcoming under Nixon. Demands from the South Vietnamese were increased. With three days to go before the 1968 Presidential election, the South Vietnamese withdrew from peace talks and they collapsed.

Chennault was no stranger to world affairs. In 1947 she had married Claire Chennault, a World War II aviation hero, and since that time had been an influential journalist and right-wing political operative. Born in Beijing, she took intense interest in Asian and Chinese affairs and was a staunch hawk on the Vietnam issue.

Chennault either did or didn't proceed with direct orders from Henry Kissinger and the Nixon campaign. What exactly happened in this regard was the subject of much dispute at the time (though it increasingly appears that Kissinger at the very least was communicating with Chennault). What is known for sure is that she was quite persuasive, and was able to (falsely) convince many within the South Vietnamese government that Nixon was prepared to extract a much better deal on their behalf.

No matter the cause, when the South Vietnamese announced that there was no peace plan, the momentum of Hubert Humphrey collapsed. Coming two days after Lyndon Johnson's announcement, this rebuke served as the President's final humiliation on the issue of Vietnam. He retired to Texas as a defeated man, and was not above accusing Richard Nixon of treason in private conversations.

The legacy of Nixon's comeback

To this day, the entire episode has been strangely overlooked in the American political memory. If anything, on the face of it, the sabotage of Vietnamese negotiations by a private citizen was certainly a greater crime than Watergate.

The Democrats were aware of Chennault's intrigues. For the final three days of the campaign Nixon's team braced itself for an onslaught of invective from Hubert Humphrey exposing this manipulation and sabotage of the peace talks -- invective that would clinch the election in favor of Humphrey and exile Nixon to his final, ignominious retirement. But Humphrey never attacked.

The matter was the subject of a direct phone conversation between Nixon and Lyndon Johnson in which Nixon swore that Chennault had been a rogue operative. In a controversial decision (many Democrats implored him to attack), Hubert Humphrey chose to accept Nixon's assurances. Was Nixon truly ignorant to the movements of Anna Chennault?

For his part, Nixon reportedly broke into a rage when news of Chennault's maneuver broke amongst the higher levels of the government. Theodore White, an omnipresent journalist and consummate liberal, asserted in 1969 that, "The fury and dismay at Nixon's headquarters when his aides discovered the report were so intense that they could not have been feigned simply for the benefit of this reporter."

In light of further developments in Nixon's career, is it possible to accept White's conclusions? Surely a much different attitude prevailed about Nixon in 1969 than would come to the forefront over the next few years.

The collapse of the peace talks was devastating for Humphrey. In the actual voting, he underperformed the final polls by about three points. Nixon's possible duplicity was not aired to the American public and he won the election by 400,000 votes. Had Humphrey made an issue of Chennault's interference, the outcome might well have been quite different. In the realm of late-election turns there is little that can match the opaque volatility of the 1968 campaign.

Recommendations/Sources

- Secret of '68

- Theodore White - The Making of the President 1968 (Landmark Political)

- Rick Perlstein - Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America