Education and Religion -- The Black Community in Reconstruction

Dan Bryan, February 26 2012

Freedom to worship after slavery

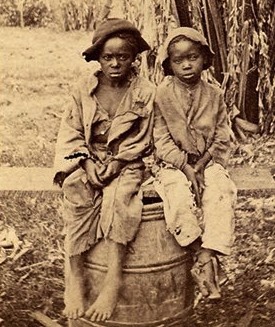

In the midst of the drought and devastation of 1865, the black people formed new churches.

Before the war, in most parts of the south, slaves were forbidden to hold services without a white minister present. In the typical plantation church, whites sat in front and slaves sat or stood in the back. The doctrines preached were infused with the assumption of white supremacy, and of servility to this order.

These churches quickly became the center of the new black communities. They served as community centers and mutual aid societies in addition to their religious role. They fought for the education of the black people. To the extent that blacks held elective office in the first years after the war, their leaders overwhelmingly originated from the churches.

These churches also worked with the Freedman's Bureau to create many of the first black schools after the Civil War.

The Freedman's Bureau and the first black schools

Reading and education were the great desire of the freed slaves. There were old women who wanted to read the Bible before they died. There were mothers who wanted their kids to have a better life. All of them studied profusely.

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands -- usually called the Freedman's Bureau -- was a federal bureau created to assist the freed slaves in their transition to citizenship. Besides providing food rations to prevent starvation, a key focus of the Bureau was education. The Bureau worked with the black churches to locate suitable teachers, to provide funds for schools, and eventually to create colleges which were heavily focused on the training of future educators.

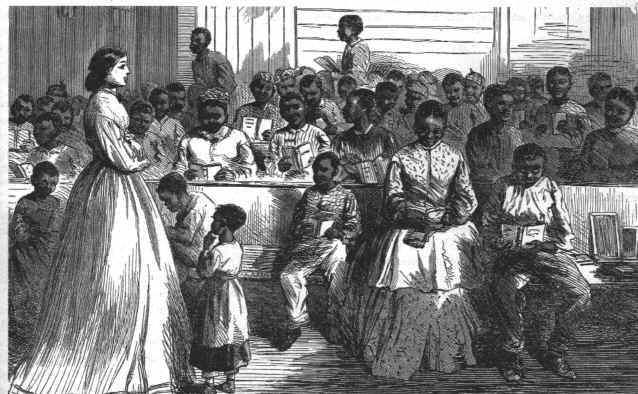

Doing any of this in the south of the 1860s was no small feat. In the years after the civil war, no state in the entire south had a system of universal, state-funded education. With a few exceptions, southern whites refused to teach the children (particularly under the auspices of the despised Freedman's Bureau). In the immediate aftermath of emancipation, there was a shortage of qualified black teachers. One solution lay in finding educators from the north.

For many in the abolitionist movement, the impulse for education was a natural extension of their agitation for the end of slavery. Vast numbers of benevolent societies had been established in the north, and assisting with the education of the former slaves was obvious. Though they were numerous, the American Missionary Association was probably the most prominent of them. Together, these organizations sent thousands of young teachers into the south.

Most of them were young, unmarried, well-educated women from middle-class homes. They carried with them to the south a philosophy of hard-working individualism, mixed with a deeply Christian sense of social responsibility. Southern whites found plenty to complain about in their supposed naivete and meddlesome ways. A common complaint was that the freed slaves became insolent as the Freedman's Bureau educated them in the ways of radicalism.

The creation of the black universities in the south

No matter how well intended the efforts of the northern teachers were, logistics did not favor them as a long term solution. Those who were concerned about black literacy quickly realized that a massive number of teachers would be needed to fill this need, and that they would have to come from the black community in the south.

Thus, it was in the years immediately after the war that famous institutions such as Morehouse College, Fisk University, Howard University, and Alcorn State were established. A great number of smaller colleges can be added to this list as well. Over the years, they graduated thousands of teachers who formed the backbone of the black education system. As a whole, on tight finances, they responded admirably to the need which had presented itself. Illiteracy among the black community dropped sharply from its heights at the dawn of emancipation.

Hiram Revels -- portrait of a black leader

The black churches produced the first generation of political leaders in the black community. Hiram Revels was one of them. Born a free man in North Carolina, he became a preacher and ended up in Natchez, Mississippi by the late 1860s. According to contemporary accounts, he was impressive enough in intelligence and oratorical ability that the Mississippi State Senate was moved to nominate him for a U.S. Senate seat.

On February 23, 1870, Revels took his seat in the United States Senate, becoming the first black man to occupy a seat in either house of the U.S. Congress. In comparison to some Republicans, he took a fairly moderate stance on the issues of Reconstruction. When his term was finished, he became the President of Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College, which would one day become Alcorn State University.

Revels was hardly the only black man to achieve political prominence in the Reconstruction south. Generally the most important slots were reserved for former Union Army officers, or other well connected "carpetbaggers". Further down the ticket, the majority of the lesser offices would be filled with leaders of the black community. This became a winning coalition in the early days of Reconstruction, and the Republicans tried to keep this formula in place for as long as they could.

Recommendations/Sources

- John Hope Franklin - Reconstruction after the Civil War

- Eric Foner - Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877

- Frank E. Smith - The Yazoo River

- Hans Louis Trefousse - Thaddeus Stevens