Lincoln, McClellan, 1862, and the Great Mistake

Dan Bryan, February 23 2015

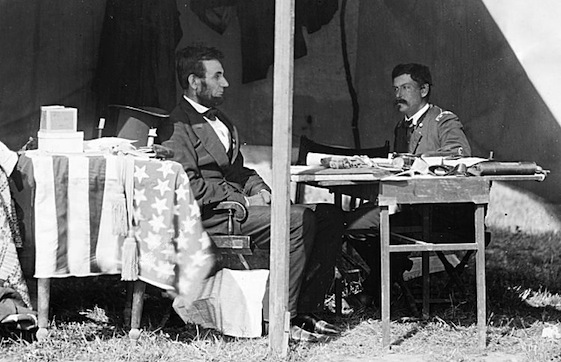

Abraham Lincoln and George McClellan are photographed in 1862 after a meeting.

Abraham Lincoln and George McClellan are photographed in 1862 after a meeting.Even though the Union failed to achieve a total victory in early 1862, its Army of the Potomac had achieved an enviable strategic position against the Confederacy. It stood perched at the very edge of Richmond in substantial numbers, and had fought off several Confederate attempts to repulse it. However, the Union Army was hamstrung by abundant caution, political constraints, and an aversion to fixed entrenchments and battles of attrition. The latter was the likely outcome of holding fixed lines so near to Richmond. Both Abraham Lincoln and George McClellan thus agreed on withdrawing these troops. Ironically, this cautious attitude likely prolonged the Civil War and increased the ultimate price of victory.

The Anaconda Plan of Winfield Scott: a Rejected Strategy

In the first days of the Civil War, an aging General Winfield Scott presented his plan for victory to Abraham Lincoln and George McClellan. It called for a full naval blockade of the South, in combination with an offensive down the length of the Mississippi River. The South would then be cut off from outside supply and would slowly wither until it sought peace. This strategy was known as the "Anaconda Plan".

People in the North were not eager to hear this advice in 1861. The expectation was that a quick, decisive victory would be achieved the first time the two sides met in the field. Lincoln's initial call for volunteers was for a mere ninety days. This was the popular and expedient move at the time. As in many other things, people wanted the benefits of a decisive victory without enduring any of the potential costs. Lincoln immediately sent the green Northern army on its way to Richmond over its commander, Irvin McDowell's objections. Washington's high society turned out in carriages to watch the first battle at a place called Bull Run, expecting an easy victory for the North.

After the debacle at the First Bull Run, attitudes changed some. A larger army was enlisted and placed under the command of George McClellan. It was put through a period of intense training and prepared for a larger offensive in 1862. This offensive was initially promising, but inability to accept a long, drawn out war ultimately sabotaged it short of success. While McClellan's reticence certainly contributed, just as important were the political considerations of Lincoln.

The Peninsula Campaign and the Caution of McClellan

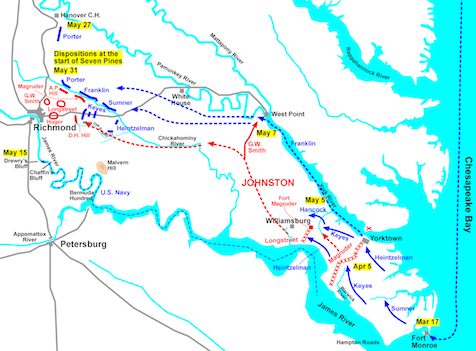

McClellan's strategy and offensive in early 1862 became known as the Peninsula Campaign. It was a roundabout, overcomplicated plan. It involved an amphibious landing near the tip of the peninsula between the James and York rivers and a march to Richmond from the east, with the hope of circumventing the main Confederate army. It failed to achieve these immediate aims. McClellan immediately ran into Confederate troops and moved slowly upon landing. Faulty intelligence and McClellan's own pessimism greatly exaggerated the number of these opposing forces. Such estimates were used to justify a slow march, giving the Confederates plenty of time to prepare a defense of Richmond.

Even so, by June the Union Army was within a few miles of Richmond and was pressing down on inferior numbers of Confederate troops. At the end of that month the Confederates, under the new command of Robert E. Lee, launched a series of sharp attacks which led to the Seven Days' Battles: notably Gaines's Mill and Malvern Hill. Tactically these attacks generally failed and the Union troops maintained their position around Richmond. So long as they remained in this spot, the ability of the Confederate Army to move out and launch large attacks was compromised. They would need always to maintain a large contingent in front of their capital -- a contingent that would be immobilized.

The Seven Days' Battles were expensive for Lee as well. He lost more men in battle than the Union and his army ultimately had many fewer men to draw upon. While the immediate effect of these casualties was small, they foreshadowed much bigger problems that would eventually beset Lee and the Confederacy. McClellan and Lincoln failed to appreciate these advantages in 1862.

Lincoln, McClellan, Politics, and the Union Withdrawal

McClellan was rattled by the Confederate counterattack and constantly feared that his larger army was on the verge of being overwhelmed. Lincoln was overly concerned with the approach to Washington D.C., envisaging political catastrophe if even a small number of Confederates approached the city. Thus, shortly after the Seven Days Battles, the main force of the Army of the Potomac withdrew back to Washington to block any potential approach. Of course General Lee, realizing that Richmond was no longer under threat, immediately undertook the very attack that the Union was guarding against, leading to his victory at the Second Bull Run.

Lincoln had myriad political considerations in this period. To gain the largest possible support for the war, he had sold it as a limited campaign. Union Army units were all volunteer. Many generals were selected based on political power they held in their respective states. Strategically, the Union was simply trying to meet the Confederate army in the field and defeat it. There was not yet the maneuvering in place to gradually wear down the Confederate forces and bring them to terms, because the very idea of a gradual victory was still anathema. Lincoln's opponents -- border state men, peace Democrats, and so on -- were waiting to pounce on any sign of Confederate success so they could discredit the war effort. Any rebel march on Washington D.C., even with a mere handful of troops, could have raised a media frenzy and led to problems for Lincoln and the Republicans in the 1862 elections. In Congress the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War watched over the Union's every move from the radical Republican perspective, evaluating generals based on their political beliefs. All of these political considerations were counterproductive. They held the Union back from exploiting its natural advantages in men and resources, and caused it to undertake an overly cautious strategy.

Once the Union Army was removed from Richmond, Robert E. Lee was given the freedom to maneuver his army into offensive positions. This state of tactical flux was a huge asset for Lee's smaller army and his creative mind. Over the next year he ran through several fantastic victories, culminating in Chancellorsville and the invasion of Pennsylvania in 1863. It was only after Lee was stopped at Gettysburg and Ulysses Grant took command of the Union Army, that the Union regained its initiative and pressed down again upon the heart of Virginia. In this interval the war had escalated into full scale mobilization, a military draft, the deaths of tens of thousands of soldiers, and much destroyed countryside.

A Long War Nonetheless

Lincoln and McClellan's decision to have the Union forces withdraw from the vicinity of Richmond shows, even a year after the war began, how alluring the idea of a decisive Union victory on the battlefield was to the Union establishment. They were simply unprepared to accept a long, "anaconda-like" siege of Richmond as a route to victory. In this they were in line with the overwhelming sentiment of the North in the early days of the Civil War.

Ironically, by holding out hope of winning a single, ultimate battle, Lincoln and McClellan gave up their real strategic advantage and ensured that the war would last much longer than it needed to. The fact that the war in the east was ultimately won, in early 1865, after a prolonged entrenchment at Petersburg and Richmond only underscores this point. There was little that could have prevented the Union from undertaking this identical strategy in 1862, and much loss of life and rancor might have been saved in the process.

There is a lesson in this that can be applied to other areas of military strategy, politics, or even life in general. The failure to be realistic about the full extent of a problem -- in this case, the actual strength and viability of the Confederacy -- led to half-measures and ultimately to a much greater cost than would have been suffered with an immediate, vigorous effort.

Recommendations/Sources

- Stephen W. Sears - To the Gates of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign

- Kevin Dougherty and J. Michael Moore - The Peninsula Campaign of 1862: A Military Analysis

- Stephen W. Sears - George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon