The Cherokee Acculturation

Dan Bryan, March 26 2012

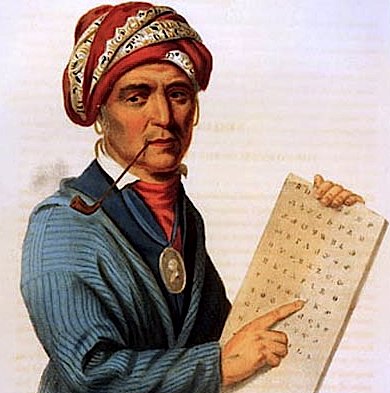

Sequoyah -- creator of the Cherokee writing system.

Sequoyah -- creator of the Cherokee writing system."They (the Cherokee) said they would follow the advice of their great father General Washington, they would plant cotton and be prepared for spinning as soon as they could make it, and they hoped they might get some wheels and cards as soon as they should be ready for them..." - Benjamin Hawkins (1796)

The Cherokee had lost so much land by the early 1800s that many could tell their efforts at active resistance were of no use. At the same time, sympathetic voices emerged in the new government, led by the first President of the new country. George Washington was more or less sympathetic to the Indian tribes, including the Cherokee, and his great hope was that their society might be modernized and assimilated into American society at large.

Washington believed that with the proper example, the Indians could become social equals of the whites. He envisioned them adopting Christianity, modern agriculture, constitutional government, writing, patriarchy, property rights, and in general all the other cultural traits that marked the superiority of the new nation. To this end, government agents were sent to live among the Indians, so that they might lead by example.

No tribe heeded the advice of President Washington more than the Cherokee. Over the last years of the eighteenth century, their society completed an almost total transformation into a landed, agrarian society.

Plantations and slavery amongst the Cherokee

The Cherokees had owned and traded slaves since around 1700, but they had been used within the context of traditional village life. As the 1700s approached their end however, the Cherokee people turned increasingly to the cultivation of cotton.

In 1797, President Adams appointed Silas Dinsmoore as an agent for the Cherokee tribe, and he assisted them in the process of growing cotton, and taught the women how to spin and weave cotton fibers.

As individual ownership took precedence, plantations emerged on the Cherokee lands in Georgia. Many of these were owned by a mixed-blood elite, the progeny of unions between traders and Cherokee women of earlier generations.

Two Moravian missionaries toured the Cherokee country in 1799 and found such practices well established. At this time there were many orchards, and fenced off fields of corn, wheat, and cotton. There were looms where the cotton was processed. There were also large numbers of horses, cattle, and pigs.

The land for these farms and plantations was still owned by the tribe, but any improvements were the property of the individual who made them. Unclaimed land could be occupied without charge by any Cherokee who made the effort to clear it.

A conservative Cherokee backlash to the new lifestyle

Not all Cherokees lived as such. The more conservative elements still lived in the hills, and they disdained the mixed-bloods, the loss of traditions, and the dependency on cash crops. These Cherokee were full-blooded and still hunted in the hills as their ancestors had.

The appearance of a northern Indian called Tecumseh in 1811 brought these groups into open conflict. Tecumseh's philosophy could hardly have been more aligned with the full-blooded conservatives. His agenda was the creation of an Indian confederacy, an end to warfare between Indian tribes, and a unified defense against white settlements. He also called for an abandonment of white practices and a return to hunting and gathering as a way of life. The Cherokee who farmed on plantations had no interest in this message.

Inspired by Tecumseh, an old Cherokee prophet known only as "Charlie" gave a speech at one of their meetings in which the conservatives where incited into a frenzy. He called on the Cherokee to dispose of their iron pots, their knives, their beads, and their white man's clothes. He told them to kill their cattle and their hogs. He let them know that the spirits would abandon them for living as the white man lived.

Charlie won some support, but the Cherokee as a whole did not join Tecumseh.

An even greater assimilation effort

Neither did the Cherokee side with the British in the War of 1812, for once making the right choice. The Creeks, their traditional enemy, did side with both Tecumseh and the British, and the Cherokee helped an American general named Andrew Jackson in his campaigns to subdue the Creeks.

After the war, gratitude from General Jackson was not forthcoming. In 1817, he proposed that the Cherokee sign over all of their land in Georgia and Tennessee in return for unoccupied land in the west, to be held in perpetuity. Outrage was the reaction from the Cherokee. Jackson was forced to back off by his superiors, but his heart remained unchanged.

By 1819, even more treaties had been signed. Again the tools of negotiation were threats, force, and bribery. Those who assisted in drawing concessions were generally enriched, while the tribe as a whole was threatened with expulsion and attack if they resisted.

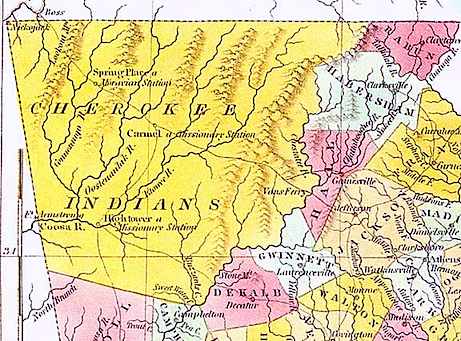

Cherokee land remaining in Georgia (c. 1820)

Cherokee land remaining in Georgia (c. 1820)It was at this point in time that the lowlanders in Georgia -- those who were the most prosperous and assimilated -- made a conscious effort to adapt American culture in nearly every way. Their great hope was that they might someday be seen as equals to the whites, and be allowed to keep their land.

Schools, churches, dress, and literacy

In outward appearance the Cherokee aimed to imitate the whites. They disregarded their old clothing completely, and wore the suits and dresses of their neighbors. They built houses like those of the whites and stocked them with wooden furniture and other such implements.

Missionaries had lived among the Cherokee for some time, but now that tribe took up the practice of the Christian faith with a new ardor. They made more of a point of attending church, and they brought their slaves as well and allowed them more exposure to the faith.

Mission schools were built in large numbers and the Cherokee put more of an emphasis on a well-rounded education. The most prosperous landowners even sent their children to private schools in the north, where they learned to read and write in the English language. Knowledge and literacy expanded, especially among the youth.

In 1821, Sequoyah completed a Cherokee syllabary with 86 characters. It was not an easy task to complete. At first, Sequoyah envisioned a system much like Chinese, with a symbol for every word in the language. He became obsessed with perfecting the system, to the point that he neglected his crops. His neighbors became convinced that he was insane, and his wife burned his work in frustration, believing it to be witchcraft. When the syllabary was completed, other Cherokee took it to be sorcery at first and refused to believe in its usefulness.

Despite these obstacles, Sequoyah found his vindication. By 1825 the syllabary was in general use, and the Cherokee were in all likelihood more literate than the whites who lived around them, if anecdotal evidence may be admitted here.

Elias Boudinot was an advocate for Cherokee literacy and education. He is also an example of how the Cherokee adapted their dress and appearance in the early 1800s.

Elias Boudinot was an advocate for Cherokee literacy and education. He is also an example of how the Cherokee adapted their dress and appearance in the early 1800s.A Cherokee named Elias Boudinot (not to be confused with the New Jersey constitutional delegate) took up the work of Sequoyah and translated the New Testament into the new written language. He then worked on the founding of the Cherokee Phoenix and became its first editor. In his work to gain funding for this newspaper, Boudinot toured the the northeast and gave speaking engagements, building support for the Cherokee cause in that region. At this he was quite successful.

The Cherokee Constitution of 1827

Most ambitiously, the Cherokee nation wrote a constitution and adopted it in 1827. It was modeled almost entirely on the United States Constitution, with a judicial, legislative, and executive branch. A capital was established at New Echota. The capital building had two stories, brick chimneys with fireplaces, a plank floor, glass windows, and a staircase. John Ross was appointed their Principal Chief, equivalent to President. They set up eight judicial districts and a bicameral congress. All of this for a population of about 20,000 people living in an area a fraction of the size of Georgia.

Such were the heights of Cherokee acculturation. If their strategy was to prove that they could be "civilized" in the same way as the whites, they could hardly have executed it better and more thoroughly.

Recommendations/Sources

- "The Cherokee Nation official website and history"

- Robert J. Conley - The Cherokee Nation: A History

- Grace Steele Woodward - The Cherokees (The Civilization of the American Indian Series)

- R. Halliburton Jr. - Red over Black: Black Slavery Among the Cherokee Indians (Contributions in Afro-American and African Studies)