Indian Removal and the Trail of Tears

Dan Bryan, March 26 2012

Throughout 1838, Cherokee were evicted from their homes in Georgia by federal troops and militia. (Painting by Max Standley)

Throughout 1838, Cherokee were evicted from their homes in Georgia by federal troops and militia. (Painting by Max Standley)The joy of a new constitution was short-lived, for 1828 was the year that sealed the Cherokees' doom.

It was probably just a matter of time in the first place, but the twin blows of the Georgia Gold Rush and the election of Andrew Jackson made their extinction or resettlement an inevitability.

The Georgia Gold Rush and the Georgia Gold Lottery

In 1828 a great gold rush began in Georgia, and its epicenter was right in the midst of Cherokee territory. The immediate consequences were an influx of squatters, illegal mining, and forced evictions of Cherokee from their plots.

The state government of Georgia supported its own citizens to the hilt. They passed laws making it illegal for the Cherokee to dig for gold -- on their own land -- and sent a militia to enforce the "rights" of Georgia's whites who were flooding into the area.

Poorly educated, dirty, and cruel by nature, the Georgia Guard pushed the Cherokee out of their homes with rifles and sticks wherever there seemed to be gold.

Things went even one step further in 1832. The state government divided the Cherokee land into forty acre plots and drew them out in a lottery. Even though there was no basis for parceling out the land in such a way, even more white settlers flooded into the Cherokee lands, looking for "their" lots and the gold that lay beneath.

The election of (the Cherokee hating) Andrew Jackson

Even worse for the Cherokee, 1828 was the year in which Andrew Jackson was elected President of the United States.

Not only did President Jackson have ill motives towards the Cherokee, his very livelihood and fortune had come at their expense. Orphaned at 14, Jackson moved to Tennessee penniless at the age of 20, before the territory had a name, and became a lawyer, a planter, and a land speculator. He was one of the frontier hustlers who had grown rich through the gradual appropriation of land from the Cherokee and other tribes.

In the 1790s, Jackson had ridiculed Washington's respect for the Indians and called for his impeachment. He had cheated them on numerous treaties, and he generally considered them to be of subhuman origin. Their pretenses of constitutional government and civilization he found to be preposterous.

It's no exaggeration to state that out of any politician in the entire United States who could have ascended to the Presidency, Jackson was the worst possible result for the Cherokee. Even Davy Crockett, whose own grandparents had been scalped by that tribe, supported them over the policies of Jackson.

Jackson was not alone, however. He represented the white masses of the south and was one of them (albeit as a wealthy exemplar). When they looked at the Cherokee society with the eight judicial districts and the bicameral legislature, they saw only farce. They saw a group of children playing house, imitating without understanding. They wanted Cherokee gold and Cherokee land, and Andrew Jackson was of one mind with their desires.

The legal basis for the Trail of Tears

Jackson pushed the Indian Removal Act and it passed in 1830 by a congressional vote of 102-97. It authorized the President to grant lands in the west in return for the removal of the eastern Indian tribes, and supporters and opponents alike were sure that Jackson would make good upon the powers granted.

The vote itself was highly contentious, and many in New England and the east coast were outraged by the brutality of Jackson and his southern allies. No doubt their motives were pure, but it should be remembered that their own ancestors had annihilated many tribes on the east coast, to the point where zero survived.

There was a Supreme Court decision in this time that seems to be misrepresented in some texts -- Worcester v. Georgia. A common retelling has it that Justice Marshall forbade the government from removing the Indians. When Jackson heard of the decision, his quote was: "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!"

Jackson then had the Cherokee removed in violation of the Court's ruling, to hear it told in many history books.

The reality is more nuanced. All this decision did was to remove the power of the states to pass laws affecting the Indians, and to reassert the Indian tribes' rights as sovereign nations. Now it is true that Georgia ignored the ruling entirely, and continued to enforce absurd laws like the Gold Lottery in 1832, but the impetus for their physical removal to Oklahoma was a matter for the federal government, and was not affected by the court's decision.

Thus, the next step was to negotiate a removal treaty with the Cherokee. Unfortunately for the Cherokee, Jackson as a general had extensive experience in negotiating dubious treaties with the Indians. There was a section of the Cherokee elite that feared the inevitability of removal, and turned their focus towards extracting concessions for a voluntary treaty.

Jackson turned his attention towards this group, and the result was the Treaty of New Echota. Signed with a minority faction of Cherokee, disavowed by their Principal Chief John Ross, and passed through the Senate by a single vote, this treaty became the legal basis for removal.

In 1838, 7,000 federal troops and militia under General Winfield Scott were dispatched to Georgia to commence with the removal process.

The Trail of Tears

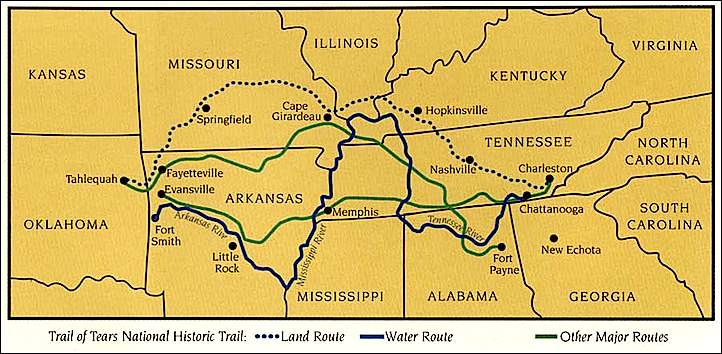

Approximate map of the Cherokees' Trail of Tears, 1838-1839

Approximate map of the Cherokees' Trail of Tears, 1838-1839The first order of business was to evict the Cherokee from their homes, and to concentrate them into centralized internment camps. About 16,000 Cherokee were rounded up and marched a short distance into Tennessee, where they waited for the longer march into Oklahoma.

It is said that an atmosphere of despair prevailed within these camps. Whiskey traders were smuggled their wares and many Cherokee saw no option but to drown their sorrows. Missionaries witnessed the Christian training of the young girls melt away as the traders plied them with booze and imposed themselves.

Dysentery broke out in the camps and people began to die. The initial plan had been to transport the Cherokee via riverboat, but drought had reduced the water levels of the Tennessee River enough to make this impracticable. Only a few proceeded by this water route -- the rest marched overland for a thousand miles.

On this march the Cherokee frequently found themselves sick, short of food, unsheltered, under clothed, and dispirited. Winter set in, and the ice and snow began, for their route had taken them north through southern Illinois and Missouri. Many groups found themselves stranded and exposed at the river crossings for some time. All of these hardships were borne by grown men, women children, and the infirm alike.

About four thousand Cherokee died on this march, and untold centuries of continuity on the land of the southeast had been destroyed. To this day, Jackson's name has forever been attached to the stain of this policy.

Recommendations/Sources

- "The Cherokee Nation official website and history"

- Robert J. Conley - The Cherokee Nation: A History

- Grace Steele Woodward - The Cherokees (The Civilization of the American Indian Series)

- R. Halliburton Jr. - Red over Black: Black Slavery Among the Cherokee Indians (Contributions in Afro-American and African Studies)